Lāna‘i Loses The Island’s Only State Mental Health Counselor — Again

Key mental health worker on Lānaʻi resigns, eroding in-person patient care and exposing the fragility of a system that depends so heavily on one worker.

Key mental health worker on Lānaʻi resigns, eroding in-person patient care and exposing the fragility of a system that depends so heavily on one worker.

Lānaʻi residents with severe psychiatric conditions lost crucial support this month when the only on-island employee of the state agency charged with their care resigned, citing a lack of resources to carry out her duties.

The departure of case manager Kori Kuaana leaves no full-time staff physically on Lānaʻi within the Hawai‘i Health Department’s Adult Mental Health Division to help patients with diagnoses that range from depression to schizoaffective disorder manage their symptoms in between their monthly visits from a Maui-based nurse and quarterly visits from a Maui-based psychiatrist.

The division is the state provider of psychiatric and social services for uninsured or underinsured adults with a serious mental illness, including 16 Lānaʻi patients. Kuaana, who held the Lānaʻi case manager position for two years, worked her final day on April 4. While the position is vacant, a case manager based on Maui is scheduled to visit Lānaʻi twice a month. Telehealth appointments are also available.

“Our community needs and likes the consistency of having somebody they can come in and talk to,” Kuaana said. “The concern is patients will regress in their treatment.”

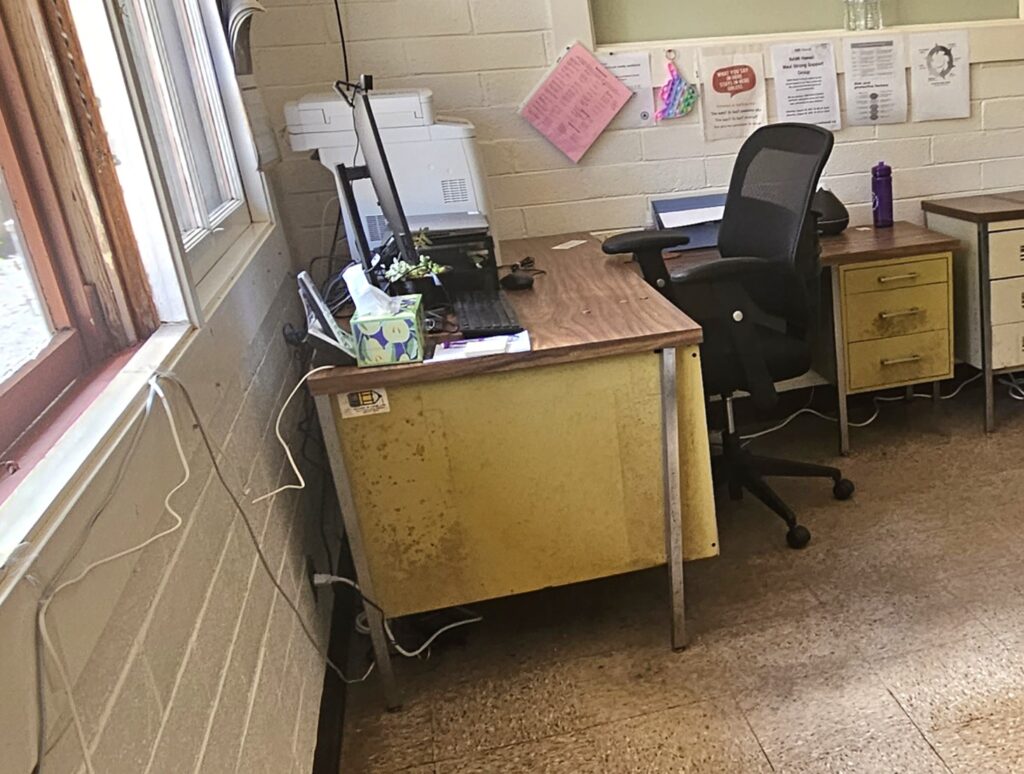

She attributes her decision to quit to a series of disputes with Adult Mental Health Division managers over what she described as unsafe workplace conditions, such as a broken desk and mold in her office. She filed a complaint with Hawai‘i’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and also cited a lack of adequate resources, including a faulty printer, the absence of a professional office cleaning service and no state vehicle for her to use to conduct weekly in-home patient visits.

Hawaiʻi Department of Health spokesman Stephen Downes said the agency does not comment on personnel matters and was unable to answer several questions about the agency’s efforts to fill the Lānaʻi case manager position. But he said the agency is actively recruiting job candidates.

Kuaana said her office desk was broken when she assumed the case manager position in April 2023. The state, she said, replaced it nearly two years later in February. The office received a new desk for the visiting nurse, a bookcase and a pair of large filing cabinets at that time.

After filing the OSHA complaint in October, Kuaana said the state hired a cleaning company that used a fungicide to mitigate the recurrence of mold in the 400-square-foot Lānaʻi Counseling Services office the state has rented since 1995.

In a letter responding to the complaint, Mary Akimo-Luʻuwai, the Adult Mental Health Division’s acting public health program manager, said there is no professional janitorial service available on Lānaʻi to clean the office space the agency leases from Pūlama Lānaʻi, the management company that oversees billionaire Larry Ellison’s 98% stake in the small island about 9 miles northwest of Maui.

Pūlama Lānaʻi was unavailable to comment Wednesday, spokeswoman Lyssa Fujie said.

Kuaana said the agency denied her travel requests to accompany a patient to Oʻahu or Maui for specialized medical care not available on Lānaʻi when the patient had no available family to accompany them. She described the medical care as critical to their mental health functioning.

“I wasn’t being supported,” Kuaana said. “There was a barrier between me and the work I was being asked to do. And there was the lack of understanding and support for Lānaʻi as a whole but specifically for those patients that receive our services.”

Prior to Kuaana’s hiring, the case manager position was vacant for nearly two years following the retirement in August 2021 of Reynold “Butch” Gima, who had held the position for 31 years. His retirement came after he was suspended for insubordination over his opposition to outsourcing mental health services for Lānaʻi patients to psychiatrists on the U.S. mainland during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

During the two-year period between Gima’s retirement and Kuaana’s hiring, two candidates accepted job offers for the case manager position but pulled out when they couldn’t find an affordable place to live on Lānaʻi. The state recruited Kuaana after Pūlama Lānaʻi reserved a housing lease to help the state mental health agency make a lasting hire.

Kuaana, who relocated to Lānaʻi from the U.S. mainland to take the position, said she plans to stay on Lānaʻi and open her own private mental health counseling service. She said she moved out of the housing unit that Pūlama Lānaʻi had reserved for her position when she started nearing the decision to quit her job.

Kuaana now lives at Lānaʻi’s new Hokuao Housing Project, a Larry Ellison-funded leased apartment complex that includes 76 affordable housing units — the first affordable units built on Lānaʻi in more than 30 years.

For decades a shortage of workforce housing on Lānaʻi has bred critical staffing vacancies that plague numerous state departments, prompting some unique solutions.

Pūlama Lānaʻi also leases units to the state Department of Education to facilitate the hiring of teachers, some of whom have been recruited from the Philippines to fill longstanding job vacancies at the island’s only grade school.

Civil Beat’s community health coverage is supported by the Atherton Family Foundation, Swayne Family Fund of Hawai‘i Community Foundation, the Cooke Foundation and Papa Ola Lōkahi.

Civil Beat’s coverage of Maui County is supported in part by a grant from the Nuestro Futuro Foundation.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

We depend on you just as much as you depend on us.

Asking for donations is never an easy task, but it’s what’s necessary to survive and thrive in today’s challenging media environment.

By supporting Civil Beat with a monthly or one-time donation, you’ll help ensure that our nonprofit newsroom has the resources it needs to remain strong for years to come. Make a gift today.

About the Author

-

Brittany Lyte is a reporter for Civil Beat. You can reach her by email at blyte@civilbeat.org

Brittany Lyte is a reporter for Civil Beat. You can reach her by email at blyte@civilbeat.org